It Pays For Companies To Leave Russia

Posted by Jeffrey A. Sonnenfeld (Yale

School of Management), on Friday, June 24, 2022

I.

Introduction and Methodology

Since Russia’s

invasion of Ukraine began in February 2022, the first author has led an

intensive effort to track the responses of well over 1,200 public and private

companies from across the globe, with almost 1,000 companies publicly announcing

they are voluntarily curtailing operations in Russia to some degree beyond the

bare minimum legally required by international sanctions.

The list has

been, and continues to be, continually updated with new additions and new

announcements by the first author’s team of two dozen experts with diverse

backgrounds in financial analysis, economics, accounting, strategy, governance,

geopolitics, and Eurasian affairs; with collective fluency in ten languages

including Russian, Ukrainian, German, French, Italian, Spanish, Chinese, Hindi,

Polish, and English. The dataset is compiled using not only public sources such

as government regulatory filings, tax documents, company statements, financial

analyst reports, earnings calls, Bloomberg, FactSet, MSCI, S&P Capital IQ,

Thomson Reuters, and business media from 166 countries; but also non-public

sources, including a sui generis global wiki-style network of 250+ company

insiders, whistleblowers and executive contacts.

When the list

was first published the week of February 28, only several dozen companies had

announced their departure from Russia. In the two months since, this list of

companies staying/leaving Russia has already garnered significant attention for

its role in helping catalyze the mass corporate exodus from Russia, with

widespread media coverage and circulation across company boardrooms, policymaker

circles, and other communities of concerned citizens around the world. The

authors have also written short editorials for The New York Times, The

Washington Post, Fortune, amongst others; each of which were the most-read

articles in their respective outlets for at least 36 hours upon publication.

In recognition

that the decision to exit Russia reflects a complex calculus for companies, with

varying degrees of actual curtailment of operations, the list consists of five

categories corresponding with an A-F letter grade scale, schoolhouse-style,

based on their level of curtailment.

-

WITHDRAWAL:

companies making a clean break/permanent exit from Russia and/or leaving

behind no operational footprint.

-

SUSPENSION:

companies temporarily suspending all or almost all Russian operations without

permanently exiting or divesting.

-

SCALING BACK:

companies suspending a significant portion (but not all) of their business in

Russia.

-

BUYING TIME:

companies pausing new investments/minor operations in Russia but largely

continuing substantive business in Russia.

-

DIGGING IN:

companies defying demands for exit or reduction of activities largely doing

business-as-usual.

Each potential

addition is carefully reviewed by a team of experts through a collaborative

process before a company is assigned a final grade through consensus and then

added to the list. The list was initially primarily focused on large US

companies with substantial exposure to Russia, but expanded over time to include

firms from across the world, particularly from Europe and Asia, as well as

public and private companies of varying size and varying presence in Russia.

Our

proprietary database has become the basis of several thoughtful research

abstracts tracking the financial response to companies’ withdrawal from Russia,

such as the 2022 Edelman Trust Barometer Special Report: The Geopolitical

Business, conducted in 14 countries with 14,000 respondents in the past month

based in part on our list of companies.

In this paper,

we seek to explore the response within financial markets, across asset classes,

to the decisions individual companies are making to either exit or remain in

Russia. This work builds on a simplified earlier version which was published in

the Washington Post. This paper amplifies the response within equity markets

through various methodological approaches to measuring total shareholder returns

by letter grade—including both market capitalization weighed returns as well as

equal weighted returns. The returns by letter grade are further measured against

variables including region (North America, Asia, and Europe), as well as market

capitalization segment (small cap, mid cap, and large cap) and sector (GICS

industry classifications). Based on the clear divergent financial performance of

companies that have withdrawn from Russia relative to those that remain, an

analysis of a representative basket of companies engaged in high-profile Russian

asset write-downs and one-time impairment charges challenges the misleading but

oft-repeated argument that the value of asset write-downs exceeds the value of

equity gains. This paper then extends the study beyond public equity markets

into credit markets through an analysis of longer dated corporate debt pricing,

credit spreads and related derivative products, showing that the investor

response has been incredibly broad-based across financial markets. Our sweeping

analysis of global capital flows demonstrates the importance investors attribute

to the decision to withdraw from Russia—and that investors believe the global

reputational risk incurred by remaining in Russia at a time when nearly 1,000

major global corporations have exited far outweigh the costs of leaving.

Clearly, doing well has not been antithetical to doing good—at least when it

comes to withdrawing from Russia.

II.

Financial Performance—Equity Markets

In this

section, we explore the financial performance, as measured through total

shareholder returns, of the companies exiting Russia relative to those remaining

in Russia. We measure performance through total shareholder returns—necessarily

excluding private companies—since other applicable metrics contain intrinsic

flaws. For example, disproportionate attention has been focused on asset

write-downs and one-time impairment charges in measuring the cost of Russian

withdrawal, though these costs only capture the loss of fixed investments in

Russia without consideration to the global reputational risk incurred by firms

that remain. Asset write-downs are also more common in capex-intensive

industries such as heavy manufacturing or commodities production but less

appropriate as a metric for measuring the performance of more human-capital

dependent industries such as professional services or software, making any

analysis based on asset-write downs inherently incomplete and incomparable

between different sectors.

Another flawed

approach in quantifying the costs to companies that have exited Russia relative

to those that remain is measuring lost Russian revenue incurred by firms

withdrawing from Russia, yet our research reveals the share of Russian revenue

as a percentage of total revenue is minimal for a majority of companies in our

dataset. Indeed, generally speaking, the lost revenue from Russian operations is

far more significant to the domestic economy of Russia—with crucial industries

ranging from automobiles to technology grinding to essentially a complete

standstill—than to the balance sheets of the companies in our dataset. Total

shareholder returns thus provides the most complete accounting of the aggregate

costs and benefits to companies from their decision to withdraw or remain in

Russia, though the metric necessarily excludes private companies for whom no

share price performance data is available. The study is thus confined to the

~600 publicly traded companies from our list.

In measuring

total shareholder returns, there are several key parameters which involve some

discretion—namely, time interval and methodology. The start date is not under

dispute. We choose to measure from the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine

onwards, and thus utilize a starting date of Wednesday February 23 at market

close reflecting the start of the invasion overnight. The end date, however,

contains more room for ambiguity. We tested two end dates—the first, through

market close April 8th, which provided a clean cut-off before the

start of 2022 Q1 earnings season, to exclude idiosyncratic moves and volatility

arising from non-Russia related earnings announcements, especially given the

significant number of FY ’22-’23 forward guidance revisions released on these

earnings calls related to more macro drivers such as inflation and growth and

liquidity. The second end date tested was through market close April 19th,

to capture a full eight weeks, equivalent to two months, from the start of the

invasion. As additional confirmation, for our overall A-F category return

calculations, we also tested a third time period of February 23rd to

March 14th, which generally tracked the steep initial market-wide

sell-off in the days immediately after Russia’s invasion, which we refer to as

the market “fall” period.

Likewise, when

measuring performance of a basket of stocks, there are two commonly accepted

methodologies. We cluster companies into five buckets aligning with the letter

grade categories assigned to companies, on the A-F scale described above, and

thus test two methodologies for computing the value of these baskets of stocks:

1) a market capitalization weighted method, also known as a market value

weighted method, in which individual companies are included in amounts that

correspond to their total market capitalization, with larger companies receiving

a higher weighting and smaller companies receiving less weighting; and 2) an

equal weighted method, in which all stocks are given the same proportional

weight regardless of size in evaluating the overall group’s performance. While

we include results for both methodologies, we advise that market capitalization

weighting is likely a more accurate representation of total category performance

reflecting actual financial markets more closely.

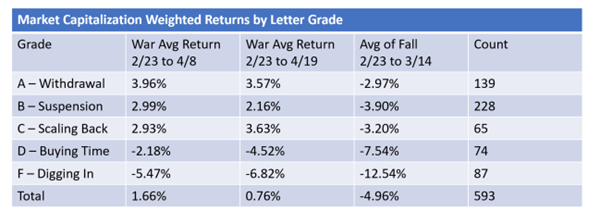

Table #1:

Market Capitalization Weighted Returns by Letter Grade Through Different Time

Periods Since Start of Russian Invasion

Table #2:

Equal Weighted Returns by Letter Grade Through Different Time Periods Since

Start of Russian Invasion

We see that

since Russia invaded Ukraine, companies that curtailed operations in Russia have

generally dramatically outperformed companies that did not, via both the market

capitalization weighting and equal weighting methodologies, and across both the

April 8th and April 19th end dates. We see this trend was

especially pronounced in the weeks immediately after the invasion, during the

“fall” period. Of particular significance is the fact that the F category

consistently underperformed all other categories by a statistically significant

degree in every trial.

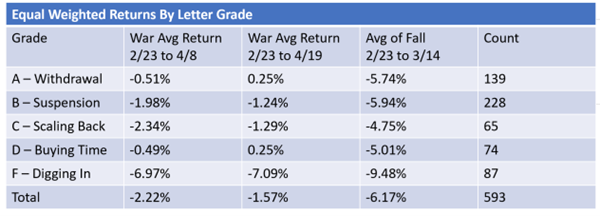

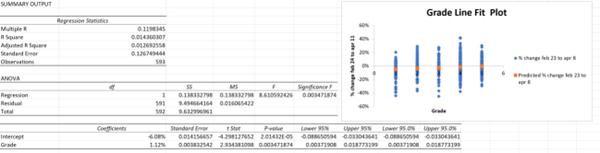

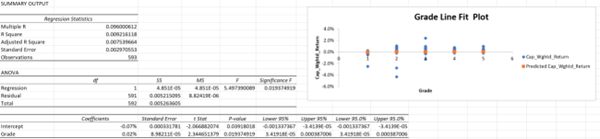

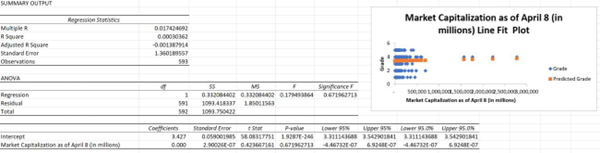

A linear

regression using (1) equal weighted returns and (2) market capitalization

weighted returns as the independent variable confirmed this trend. After

converting the A-F grades to a numeric score of 1-5 (1 = F, 5 = A) to run the

regressions, a linear regression using grades (x) and equal weighted returns (y)

yielded y=-0.06 + 0.01x. Thus, stripping away the grades in the relationship,

each company starts with a base negative return of -6%. The regression estimate

suggests that each better grade added +1.12% returns to performance, or

approximately corresponding with grade F = -5%; D = -4%; C = -3%; B = -2%; and A

= -1%. Likewise, a linear regression using grades (x) and market capitalization

weighted returns (y) yielded y=-0.07 + 0.02x, suggesting that each better grade

added 2% returns to performance when weighted by market capitalization.

Furthermore, a linear regression using grades (x) and market capitalization (y)

was not statistically significant with a p-value of 0.67 far above the 0.05

p-value threshold, confirming that size played no role in determining companies’

response to the war.

Table #3:

Linear Regression Using Grades (X) and Equal Weighted Returns (Y)

Table #4:

Linear Regression Using Grades (X) and Market Capitalization Weighted Returns

(Y)

Table #5:

Linear Regression Using Grades (X) and Market Capitalization (Y)

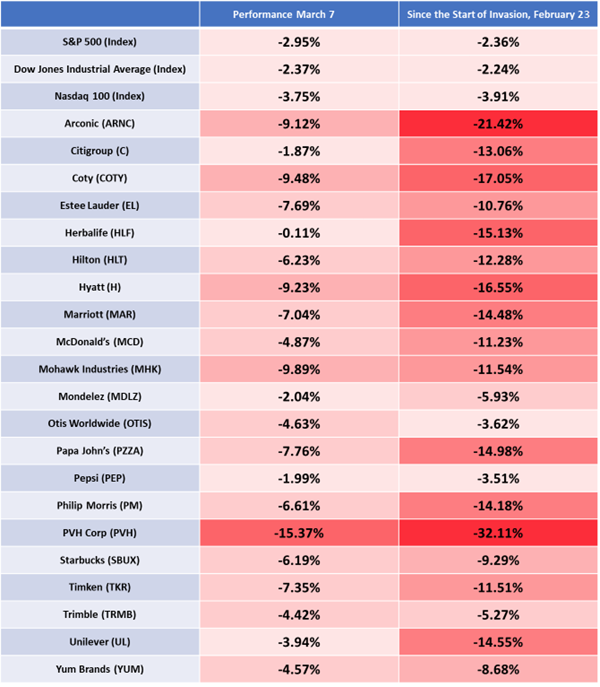

The pattern of

F companies underperforming generally aligns with our anecdotal observations

from updating the list in real-time. As soon as our list first appeared on CNBC

on March 7th, many of the companies we identified as remaining in Russia saw

their stocks plummet 15 to 30 percent, even though key market indices fell only

about 2 to 3 percent—but now our findings confirm that financial markets are

systematically rewarding companies that withdraw while punishing those that

remain.

Table #6:

Performance of New “F” Companies on March 7th, 2022, and Since Start

of Invasion Relative to Major Market Indices

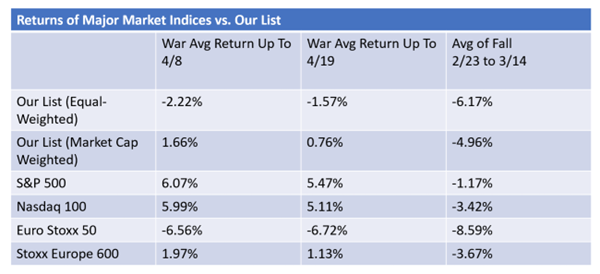

The returns

for major market indices over the same periods we tested are provided below, but

we note that by virtue of the fact our list contains publicly traded stocks

across different regions, and given highly divergent regional performance

post-invasion, it is more appropriate to benchmark companies from a specific

region to their respective region benchmark as opposed to taking the categories

in aggregate across the entire list. Thus, we provide detailed breakdowns of

performance of A category companies relative to F category companies,

cross-tabulated against region, below across both equal-weight and market-cap

weight methodologies and across various time intervals.

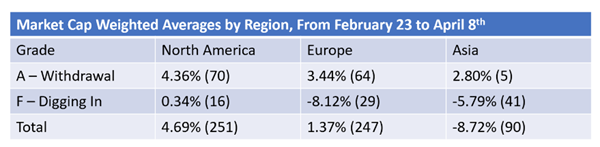

Table #7:

Returns of Major Market Indices vs. Companies On Our List Through Different Time

Periods Since Start of Russian Invasion

Table #8:

Market Capitalization Weighted Returns by Letter Grade and Region From Start of

Invasion Through April 8th

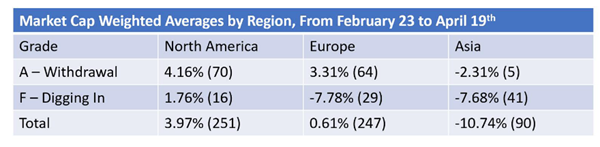

Table #9:

Market Capitalization Weighted Returns by Letter Grade and Region From Start of

Invasion Through April 19th

Table #10:

Market Capitalization Weighted Returns by Letter Grade and Region From Start of

Invasion Through April 19th

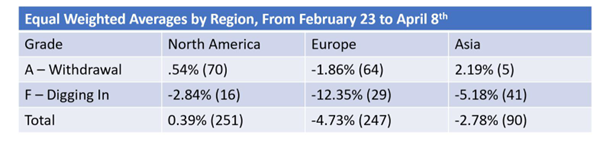

Table #11:

Equal Weighted Returns by Letter Grade and Region From Start of Invasion Through

April 8th

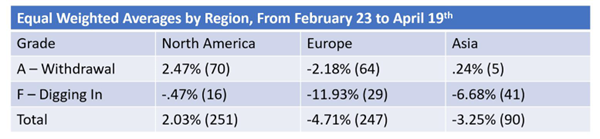

Table #12:

Equal Weighted Returns by Letter Grade and Region From Start of Invasion Through

April 19th

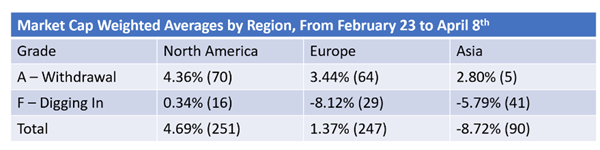

Most

significantly, we see from our regional breakdown that in every single region,

and across every time interval and methodology tested, without exception,

companies which withdrew from Russia dramatically outperformed companies which

remained in Russia, with statistically significant outperformance and

underperformance, respectively, established through regression p-values below

the 0.05 threshold—though for Asia, statistical significance was impossible to

establish given the small sample size of Asian companies that have withdrawn

from Russia publicly.

We see that

the performance by region across our list generally aligned with regional

benchmarks, though, interestingly, in North America, the companies included on

our list, in aggregate, somewhat underperformed the major indices, and likewise

with North American companies that withdrew underperforming the major indices.

Perhaps this can be explained by the number of significant components of the S&P

500 and Nasdaq 100 which did not have any exposure to Russia at all and thus

were less directly adversely impacted by the outbreak of war—as Russia

represents less than 2% of US trade in goods and services. It is conceivable

that market sentiment has been relatively lower for companies that have any

exposure to Russia relative to companies that have no direct exposure to Russia

at all, but nevertheless, the dramatic differential performance between

companies that stayed in Russia and those that left speaks for itself.

Another key

consideration beyond regional divergences is the fact our dataset of 600

publicly traded companies contains companies of all sizes. Particularly when

market-capitalization weight is used, larger-size companies can

disproportionately dominate performance results—and given our list skews towards

larger companies to begin with, with relatively fewer small companies (383 large

cap companies vs. 59 small cap companies), this bias towards large companies

disproportionately dominating results could hypothetically carry over into

equal-weighted results as well. Thus, we ran detailed breakdowns of performance

of A category companies relative to F category companies, cross-tabulated

against size as measured by market cap segment, below across both equal-weight

and market-cap weight methodologies and across various time intervals. For the

purposes of this analysis, we define small cap as any company with a market

capitalization up to $2 billion; mid cap as any company with a market

capitalization between $2 billion and $10 billion; and large cap as any company

with a market capitalization above $10 billion. All market capitalizations are

measured in USD and in the case of foreign companies, we used foreign currency

conversion rates into USD as of the end date of the time interval measured in

each trial.

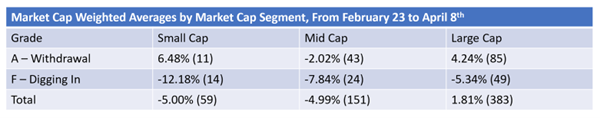

Table #13:

Market Capitalization Weighted Returns by Letter Grade and Market Capitalization

Segment, From Start of Invasion Through April 8th

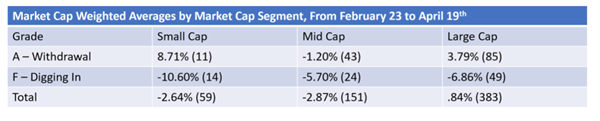

Table #14:

Market Capitalization Weighted Returns by Letter Grade and Market Capitalization

Segment, From Start of Invasion Through April 19th

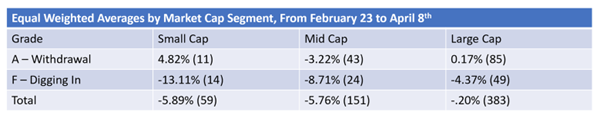

Table #15:

Equal Weighted Returns by Letter Grade and Market Capitalization Segment, From

Start of Invasion Through April 8th

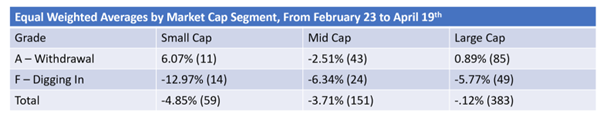

Table #16:

Equal Weighted Returns by Letter Grade and Market Capitalization Segment, From

Start of Invasion Through April 19th

Just as for

the analysis by region, we see from this breakdown by market capitalization

segment that in all three market cap segments, and across every time interval

and methodology tested, without exception, companies which withdrew from Russia

dramatically outperformed companies which remained in Russia, with statistically

significant outperformance and underperformance, respectively, once again. In

fact, the level of statistical significance is practically identical across all

three segments, suggesting that these results were not just the product of a

handful of large cap companies but rather reflects remarkable breadth and

consistency across every corner of the market, ranging from household names and

industry giants to more obscure companies. Smaller companies which might have

hoped to continue operations in Russia while flying under the radar of

investors, media, and consumers were evidently not immune to strong investor

backlash, and were comparably punished as more well-known peers in terms of

stock performance.

Another

hypothetical argument we seek to proactively dispel is that some variation in

the divergent return profiles could be hypothetically attributed to the

different sectoral composition of the companies that are leaving Russia vs. the

companies that are staying. Once more, we ran detailed breakdowns of performance

of A category companies relative to F category companies, cross-tabulated

against sector, below across both equal-weight and market-cap weight

methodologies and across various time intervals. For all sector classifications,

we deferred to the GICS standard, the industry taxonomy developed in 1999 by

MSCI and S&P for use by the global financial community consisting of sectors,

industry groups, industries and sub-industries into which all major public

companies are categorized.

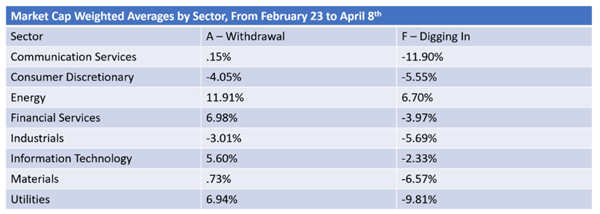

Table #17:

Market Capitalization Weighted Returns by Letter Grade and Sector, From Start of

Invasion Through April 8th

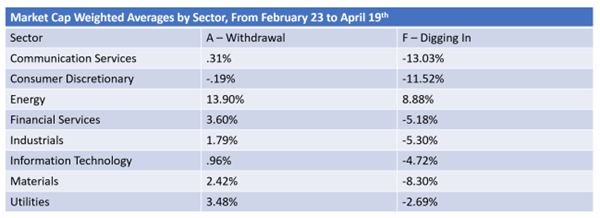

Table #18:

Market Capitalization Weighted Returns by Letter Grade and Sector, From Start of

Invasion Through April 19th

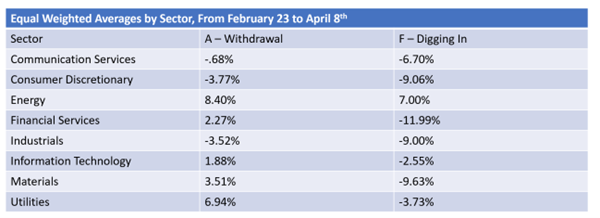

Table #19:

Equal Weighted Returns by Letter Grade and Sector, From Start of Invasion

Through April 8th

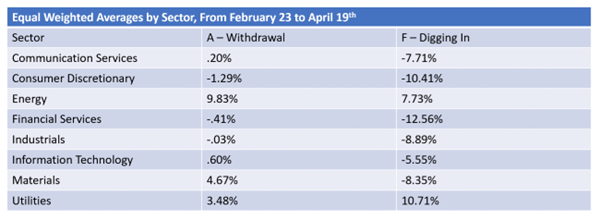

Table #20:

Equal Weighted Returns by Letter Grade and Sector, From Start of Invasion

Through April 19th

From this

breakdown by sector, across communication services, consumer discretionary,

energy, financial services, industrials, information technology, materials, and

utilities, and across every time interval and methodology tested, companies

which withdrew from Russia dramatically outperformed companies which remained in

Russia. The only exception which emerged is in the case of utilities, largely

arising from small sample size given most utilities in Russia are operated by

domestic, not foreign companies. There is only a single utility which completely

withdrew from Russia and only two utilities which remain in Russia, and one of

these remaining companies, of very small size, underwent a significant liquidity

event leading to outsized gains in mid-April and thus skewing the equal-weight

returns when measured through April 19th.

From this

analysis, it clearly emerges that shareholder returns generally correspond with

their decision to withdraw or remain in Russia, and those with an A

rating—companies which have made a clean break or permanent exit from

Russia—have performed far better than those with a F rating—companies which are

“digging in” and defying demand to reduce activities in Russia. This pattern

holds true across multiple methodologies and time intervals tested, and cannot

be explained by either regional variation, sector variation, or size variation.

Remarkably, in another variation of the same test, we found that if companies

that are undergoing special corporate actions such as M&A—and whose stocks are

being driven by idiosyncratic factors rather than broad market movements or

underlying company performance—are stripped from the dataset, the stock returns

of companies that remain in Russia exhibit even greater underperformance.

III.

Financial Performance—Wealth Creation Far Greater than Value of Asset

Write-Downs for Companies That Leave Russia

For all the

attention given to the firms that exited Russia completely and which have

incurred billions in Russian asset write-downs in the process, our research

reveals that the wealth creation driven by gains to shareholder equity far

outweigh the actual write-downs themselves.

To compare the

shareholder wealth created against the value of asset write-downs, we first

retrieved the announcement dates for the write-downs in our sample of companies.

We then retrieved the last closing stock prices prior to each announcement and

compared it to the 2/23 price to determine the stock’s “war return”. We then

compared the war returns to the respective returns since each asset write-down.

Furthermore, we obtained the market capitalization of the stock on the date

prior to each write-down announcement and multiplied it by the stock return

since the announcement in order to obtain the gain/loss in the companies’ equity

value since the announcement.

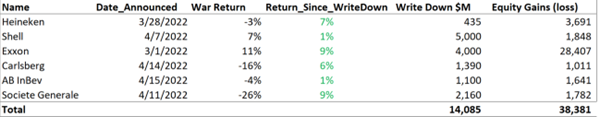

Remarkably, at

least six companies which incurred significant announced asset-write

downs—Heineken, Shell, Exxon, Carlsberg, AB InBev, and Societe Generale—have

actually seen more wealth created, far outweighing the value of the written-down

assets, when taken in aggregate. Perhaps even more surprisingly, each of these

companies had positive stock performance after the announcements of their exits

from Russia and the values of their asset write-downs—after their stocks

initially tanked in the period leading up to their announcement in most cases,

as shown by the negative “war returns” below. On balance, these companies

incurred asset write-downs of over $14 billion but have generated nearly $39

billion in subsequent equity gains. Even one high-profile idiosyncratic case not

included here, BP, is in the green on the year after incurring an unprecedented,

historic one-time impairment of $25 billion for divesting its considerable

Rosneft stake. This suggests that clearly investors are much more focused on

rewarding companies for shedding reputational risk by exiting Russia than

bemoaning the one-time impairment charges of leaving fixed assets behind.

Table #21:

Value of Overall Equity Gains vs. Losses from Russian Asset Write-Downs

IV.

Financial Performance—Credit and Derivative Markets

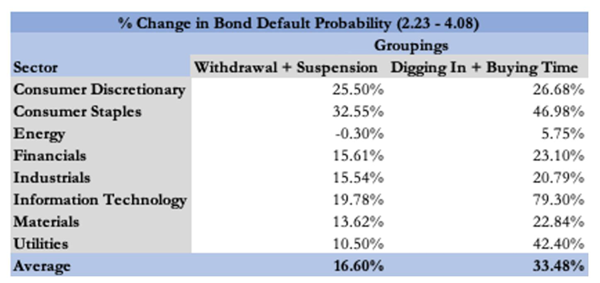

Equity markets

are not the only asset class where financial markets have clearly been rewarding

companies for leaving Russia while punishing those that remain. The same trend

is evident across credit markets—specifically the pricing of corporate debt—and

related derivative products. To evaluate the way the market was pricing the

different gradings of corporate debt in the medium to long term as well as infer

the market-implied expectation of business health, cross-tabulated against the

business exodus from Russia, we had to study changes in longer maturity

corporate debt as well as related derivative products that would enable us to

isolate and analyze individual risk factors such as liquidity or credit risk.

We chose to

study the changes in probability of default on bonds (utilizing the Bloomberg

Database) issued by corporations on our list to check for whether the expected

payoff on securities of those graded more poorly were shifting closer to the

kink and making that particular credit more information sensitive. Our thesis

was that across the majority of sectors, firms graded more poorly will suffer a

sharper increase in probability of financial difficulty if not default which

should then eventually price into credit spreads (especially as recovery rates

vis a vis Russian assets may also fall) and the credit event insurances such as

CDS or Credit Linked Notes—this is something we continue to monitor. The results

of our analysis corroborated our initial hypothesis. Although we saw a general

increase in probability of default of all corporates in our study of 500+

corporations, on a relative basis we found that across several sectors the

increase in default probability was greater for those corporates who fell into

the categories of “Digging In’ and “Buying Time’ versus those marked as

“Withdrawal’ and “Suspension’. For example, within the Financial Services

sector, the increase in bond default probability was 6.49% higher for the lower

graded pool of companies, the same trend was seen for, inter alia, Consumer

Staples, Information Technology, Materials and Energy.

Table #22:

Percentage Change in Bond Default Probability by Grade and Sector, From Start of

Invasion Through April 8th

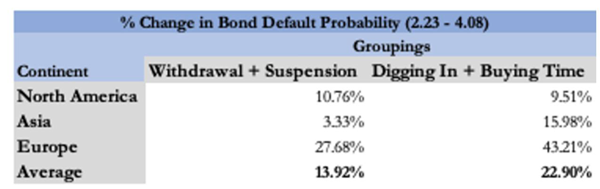

Taking a

geographic lens, we saw similarly that if bond default probabilities were

averaged across corporates on our list domiciled in North America, Europe and

Asia, those that took more stringent corporate actions such as “Withdrawal” or

“Suspension” suffered from an increase in default probabilities that was almost

8.9% smaller than for their lower graded comparable peers.

Table #23:

Percentage Change in Bond Default Probability by Grade and Region, From Start of

Invasion Through April 8th

What this data

reveals is that although the present geopolitical risk has brought into slightly

increased question the coverage capabilities of most corporations, as reflected

by the overall increase in default probabilities, those that have doubled down

on Russia have been punished by investors taking a longer term view. It seems

thus that the credit market has rewarded corporations who take a stand on this

geopolitical issue today to continue to remain in favor from an international

business perspective, as well as avoid the negative effect of international

economic sanctions, reputational risk and consumer scrutiny that will likely

weigh on those who stay quiet.

V.

Conclusion

Despite the

disproportionate attention given to the supposed losses incurred from exiting

Russian operations or from divestiture of Russia, financial markets are clearly

discounting outsized gains from exiting Russia, across asset classes, geography,

and time periods. Indeed, using our proprietary dataset tracking now well over

1,200 companies, we demonstrate that total shareholder returns since the

invasion have corresponded precisely with the level of curtailment of Russian

operations, with linear regressions revealing that each increase in letter grade

accounts for, on average, 1-2% of enhanced stock performance, dependent on

methodology. This trend cannot be explained by variations in either regional,

sector or market cap segment. Furthermore, we find that size and pre-existing

exposure to Russia played no role in determining a company’s response to the

war.

Given the

outperformance of stocks of companies that have withdrawn from Russia, the

shareholder wealth created through equity gains have already far surpassed the

cost of one-time impairments from asset write-downs across a representative

sample of high-profile companies which have engaged in Russian divestitures and

asset sales at highly discounted valuations.

We find the

pattern of financial markets rewarding companies for exiting from Russia is not

confined to only public equity markets. Our study of credit and derivative

markets, in particular longer maturity corporate debt, credit spreads, and

related credit default swap pricing, reveals a slight but statistically

significant increase in market-implied default probability of the companies that

remain in Russia relative to those that have withdrawn.

Clearly,

global capital flows across financial markets demonstrate the importance

investors attribute to the decision to withdraw from Russia. Capital allocators

clearly and unequivocally believe the risks associated with remaining in Russia

at a time when nearly 1,000 major global corporations have exited far outweigh

the costs of exiting Russia.

The complete

paper is available for download here.

|

Harvard Law School Forum

on Corporate Governance

All copyright and trademarks in content on this site are owned by

their respective owners. Other content © 2022 The President and

Fellows of Harvard College. |