THE

WALL STREET JOURNAL.

Investors everywhere think a 5-star rating from Morningstar means a

mutual fund will be a top performer—it doesn’t

By Kirsten Grind, Tom McGinty and Sarah Krouse

Millions of people trust

Morningstar Inc. to help them decide where

to put their money.

From pension funds to endowments to

financial advisers to individuals, investors rely on Morningstar’s star ratings

to help divide $16 trillion among America’s mutual funds, in much the way

shoppers use Amazon’s ratings to pick products. A lot of these investors, and

the people paid to guide them, take for granted that the number of stars awarded

to a mutual fund is a good guide to its future performance.

By and large, it isn’t.

The Wall Street Journal tested

Morningstar’s ratings by examining the performance of thousands of funds dating

back to 2003, shortly after the company began its current system. Funds that

earned high star ratings attracted the vast majority of investor dollars. Most

of them failed to perform.

Of funds awarded a coveted five-star

overall rating, only 12% did well enough over the next five years to earn a top

rating for that period; 10% performed so poorly they were branded with a

rock-bottom one-star rating.

The falloff in performance was even

more dramatic for domestic stock funds, the largest category of U.S. funds by

assets.

Billions of investor dollars hang in

the balance. Nearly every asset manager in the world pays Morningstar for data

services. Some 250,000 financial advisers rely on Morningstar’s data, services

or ratings, according to the firm. That means Morningstar’s analysis and ratings

influence investment decisions for a vast landscape of retirement plans and

brokerage accounts.

Morningstar’s reach is so pervasive

that the ecosystem for buying and selling mutual funds revolves around it. Fund

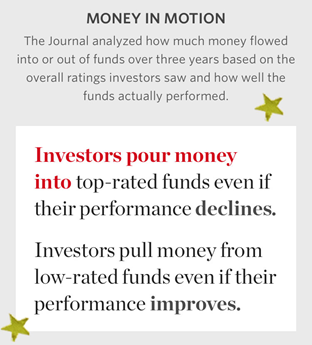

companies heavily advertise their star ratings. Money typically pours into funds

after they receive a five-star rating from Morningstar, the Journal found. It

flows out if they lose stars.

There is no question that

Morningstar has greatly improved the transparency and rigor of data on mutual

funds’ holdings and performance, making it easier for individual investors to

compare funds.

Morningstar says it has never

claimed its star ratings suggest how funds will perform in the future. The star

system is strictly backward-looking, assessing past performance, the firm says.

“We have always been very clear that it’s not intended to predict future

performance,” the company said in a written statement.

“The star rating works well when

it’s used as intended: as a first-stage screen that helps identify lower-cost,

lower-risk funds with good long-term performance,” Morningstar said. “It is not

meant to be used in isolation or as a predictive measure. Reversion to the mean

is a powerful force that can affect any investment vehicle.”

|

|

|

Notes:

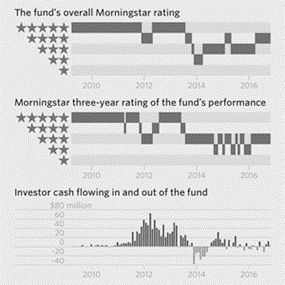

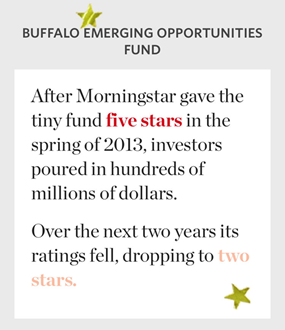

Year zero represents the initial overall rating of funds. Other points on

chart are their average star ratings for the following three, five or ten

years. Funds rated by Morningstar can have up to four ratings: a

three-year rating, a five-year rating, a 10-year rating, and an overall

rating that is based on a combination of the others.

Read the methodology. |

The firm sends conflicting signals

about the star ratings’ predictiveness. A study published by Morningstar last

month said the stars point investors to funds “likelier to outperform in the

future.”

Morningstar founder Joe Mansueto

said in an interview that the firm’s analysis of past ratings found “some modest

predictive value.” Chief Executive Kunal Kapoor, in another interview, called

the star system “a better predictor than it ever has been.”

In its written statement to the

Journal, Morningstar said its analysis has found “the Star Rating is moderately

predictive,” which “conforms to what we’d expect of a backward-looking, entirely

quantitative measure.”

The Journal’s analysis found that

most five-star funds perform somewhat better than lower-rated ones, yet on the

average, five-star funds eventually turn into merely ordinary performers.

Inside Morningstar, some employees

have expressed discomfort about how much investors rely on the ratings. Stephen

Wendel, head of behavioral science at the Chicago-based firm, wrote in the

June/July issue of Morningstar magazine that part of his job was “examining

whether we are contributing to abuses in the industry,” and said: “Morningstar’s

star ratings for funds are clearly used in the industry to imply that funds that

performed well in the past will do so in the future.”

He added, “That needs to change.”

Morningstar’s Mr. Mansueto, 61 years

old, said the star rating system “is a way to whittle down a big universe into

something more manageable.” The firm said it has worked to make investors

understand the star ratings should be just a starting point for their research.

Since 2011, Morningstar has had a

second rating system, lesser known and of limited scope, that includes analysts’

opinions. Unlike the star ratings, it is designed to be forward-looking,

Morningstar says. In this system, too, the Journal found the performance of

funds rated high, low and in between tended to converge after several years. In

addition, the Journal found Morningstar only rarely gave funds the lowest

analyst rating, “negative.”

Mr. Mansueto, growing up in suburban

Chicago, sold lemonade by the roadside before moving up to Christmas trees. At

the University of Chicago, he and a roommate sold chips and soda and advertised

by hanging posters for the “Room 607 Soda Service.” He also made his first

mutual-fund investment, with $250 from a restaurant job.

After college, he and the

ex-roommate, Kurt Hanson, started a business that provided market research for

radio stations. It surveyed listeners and created a sheet of charts detailing

their behavior. Mr. Mansueto then got a job as a financial analyst at Harris

Associates LP, a Chicago money manager.

Mutual funds were proliferating, and

a few fund managers were becoming stars, such as John Templeton and Peter Lynch.

Funds didn’t give much information about themselves, and what they provided was

opaque to nonprofessionals. Mr. Mansueto told a colleague he wanted to start a

fund newsletter in the mold of the radio-station fact sheets.

The colleague, Ralph Wanger,

cautioned that financial newsletters didn’t have a record of success. “That

turned out to be the dumbest...thing I ever said,” he recalls. “What I meant to

say was, ‘Joe, that’s the best idea I’ve ever heard—how about I quit and we go

50-50?’ ”

Mr. Mansueto launched Morningstar

from his one-bedroom apartment in 1984 with $80,000, taking the name from the

ending of Thoreau’s “Walden”: “The sun is but a morning star.”

He later spent $50,000 to hire Paul

Rand, the noted designer of

IBM’s logo, who created a signature red

font consisting of tall letters with an “O” looking like a rising sun. With

reports obtained from fund companies, Mr. Mansueto laid out data points so they

were easy to read, and advertised his reports in Barron’s.

When BusinessWeek later asked him to

devise rankings for an issue devoted to mutual funds, Mr. Mansueto began work on

what would become his five-star rating system. He toyed with using symbols

suggesting little bags of gold before deciding on stars.

Since then, assets invested in

U.S.-based mutual funds have multiplied more than forty-fold. Morningstar rode

the wave and went public in 2005.

Today, investors descend on Chicago

for Morningstar’s annual conferences, a pilgrimage for money managers and

financial advisers hoping to gather assets. At this year’s event in April,

shirtless male acrobats cartwheeled and stood on each other’s shoulders while

financiers sipped cocktails and mingled.

Morningstar groups funds into

categories based on their investing style or area, more than 100 groups in all.

It compares funds not to all other funds, nor to the overall market, but to

other funds with the same investment focus. The top 10% of funds in each group

receive five stars, the bottom 10% get one, and the rest get two, three or four

stars.

The ratings don’t reflect raw

performance, but performance adjusted for funds’ degree of risk. To make that

calculation, Morningstar uses an algorithm Mr. Mansueto devised that reflects

the variation in funds’ month-to-month returns.

The firm rates funds on how they did

over three years—plus over five years and 10 years if they’re old enough—and

assigns them an overall rating based on the others. A fund thus could have as

many as four ratings from Morningstar, though most investors see only the

overall one. New star ratings come out each month.

Most mutual funds have multiple

“classes,” each charging a different expense fee. Since varying expenses spell

varying returns, Morningstar rates each class of each fund separately.

Its star ratings covered more than

10,800 mutual funds—and almost 39,000 share classes—during the 14 years studied

by the Journal. The only qualification to be rated is being in business three

years. The ratings include index funds, which try to mimic the performance of

markets.

(The Journal’s analysis didn’t

include exchange-traded funds, or ETFs, which trade throughout the day like a

stock and usually mirror an index. Morningstar began rating ETFs alongside

ordinary mutual funds late last year, after the period covered by the Journal’s

analysis.)

Going back to 2003, the Journal

examined the rating of every investment class of every fund, in every month, and

how these changed over time—some three million records in all. (Read

the methodology.)

The Journal also reviewed

retirement-plan data, fund ads and regulatory filings, and interviewed dozens of

current and former Morningstar employees, fund officials, financial advisers and

investors.

For funds that had an overall

five-star rating at any point, the Journal found that their average Morningstar

rating for the following five years was three stars—in other words, halfway

between the top and the bottom.

When funds picked up a fifth star

for the first time during the period included in the Journal’s analysis, half of

them held on to it for just three months before their performance and rating

weakened.

The findings were especially stark

among U.S.-based domestic equity funds. Of those that merited the five-star

badge, a mere 10% earned five stars for their performance over the following

three years. Only 7% merited five stars for the following five years, and 6% did

for 10 years.

For all of the measured

periods—three, five and 10 years—five-star domestic equity funds were more

likely to turn in a one-star performance than a top one.

That means a five-star rating for

the equity funds was no more an omen of success than it was one of failure.

Morningstar’s ratings of

taxable-bond funds, which include corporate bonds and Treasurys, proved a little

more indicative of future performance. Of five-star bond funds, about 16% turned

in a five-star performance over the next five years.

Still, 8% of the five-star

taxable-bond funds performed poorly enough to merit only one star.

Hickory Hills, Ill., not far from

Morningstar’s Chicago headquarters, has a small pension fund for about 50 active

and retired police officers. In 2011, it moved about $2.1 million into the

Nuveen Santa Barbara Dividend Growth Fund, which had a five-star Morningstar

rating.

The pension board paid close heed to

star ratings. “Our brokers thought it was one of the best measurements we had

available to decide whether the fund is worth investing in,” said board

secretary Mary McDonald, referring to brokers from

Morgan Stanley.

The fund had beaten 95% of others in

Morningstar’s “large blend” category—funds that buy large-company stocks using a

blend of what investors call a “value” strategy and a “growth” strategy.

The following year, the fund beat

only 26% of similar funds, and in 2013 just 11%.

|

|

|

Notes:

Class I share class. Funds rated by Morningstar can have up to four

ratings: a three-year rating, a five-year rating, a 10-year rating, and an

overall rating that is based on a combination of the others.

Read the methodology. |

The president of the Santa Barbara

fund family, John Gomez, attributed the Dividend Growth fund’s performance to

its focus on stocks with growing dividends, not just the highest-yielding ones.

The Hickory Hills board pulled $1.2

million from the fund in 2014, and in early 2016 it took out $750,000 more. It

has since switched to a local broker, in part because of Morgan Stanley’s

reliance on Morningstar ratings, said David Wetherald, a police officer who is

also the pension board’s president.

The experience was frustrating

because “we rely a lot on the financial people. We’re not completely blind and

naive, but we’re smart enough to know that this is what they do,” Mr. Wetherald

said.

Morgan Stanley declined to comment.

Morningstar said its five-star

rating of Nuveen Santa Barbara Dividend Growth in 2011 “was an accurate

historical grade on the fund. It was not intended as or presented as a

conclusion as to what they should do.”

Morningstar also said this type of

fund generally did poorly after 2011. The example “presents an underperforming

fund in a badly underperforming category as if it’s representative of the full

rating set, which it’s not,” the firm said.

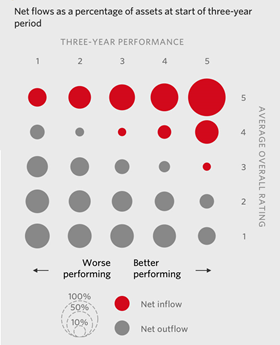

The Journal’s analysis found that

investors put new money into five-star-rated funds in 69% of the months they

held that rating, compared with 29% for one-star funds. The Hickory Hills

investment was part of $184 million investors put in the Santa Barbara fund in

2011 when it had five stars.

Morningstar acknowledged its ratings

can influence demand, though Mr. Mansueto says he believes investors typically

move money mainly based on a fund’s performance, not its star rating.

|

|

|

Note:

Funds rated by Morningstar can have up to four ratings: a three-year

rating, a five-year rating, a 10-year rating, and an overall rating that

is based on a combination of the others.

Read the methodology. |

The Journal found more than a dozen

cases where well-performing funds attracted few investors until they won a fifth

Morningstar star.

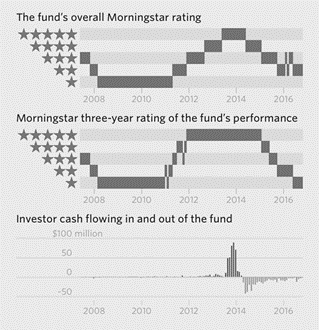

Tiny Buffalo Emerging Opportunities

Fund saw little interest despite beating many similarly focused funds over three

years, including gaining 24% in 2012. After it got a fifth star from Morningstar

in spring 2013, hundreds of millions came in, quadrupling assets to above $400

million in five months.

The small management team in

Mission, Kan., closed the fund to new investors six months later, a step

managers sometimes take when given more cash than they feel they can invest. The

Journal found many instances of funds closing after an influx that followed a

high star rating.

At Buffalo Emerging Opportunities

Fund, fortunes soon reversed. In 2014 it lost more than 7% and trailed about 95%

of other funds focused on growing small companies. Over the next two years its

Morningstar rating fell to two stars and its assets plunged to less than $100

million.

Buffalo Funds declined to comment.

|

|

|

Note:

Funds rated by Morningstar can have up to four ratings: a three-year

rating, a five-year rating, a 10-year rating, and an overall rating that

is based on a combination of the others.

Read the methodology. |

Inflows sparked by high star ratings

are especially important for managers of actively managed funds now that more

investors have migrated to passive ones that just try to match an index. On

calls with securities analysts, fund-company chiefs often trumpet how much of

their asset total is in four- and five-star funds, as a sign of the companies’

ability to attract cash.

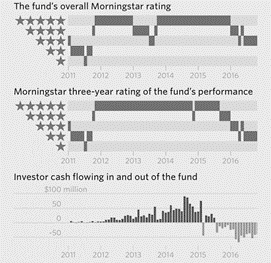

From his office park in

Mechanicsburg, Pa., financial adviser Donald DeMuth starts each workday by

logging onto Morningstar Office, which helps him organize client portfolios. He

also uses Morningstar data to check on fund performance and details such as how

rapidly a fund’s portfolio turns over.

Mr. DeMuth, 66, has used Morningstar

so long he can’t remember when he started. “With rare exception, we would want a

fund to have five stars,” he said.

In early 2012 he put some of his

clients’ money in a fund called Permanent Portfolio when it had a five-star

Morningstar rating. The fund invests across an array of assets, including gold

and silver.

Its performance had already started

to slip. By the end of 2012, it was 5 percentage points behind its Morningstar

category benchmark, the “Morningstar Moderate Target Risk,” which is a mix of

global bonds and global stocks.

Mr. DeMuth moved his clients out in

the fall of 2013, a year when the fund trailed that benchmark by 16 percentage

points. At the end of 2013, Morningstar gave the fund a one-star rating for its

performance over the prior three years.

|

|

|

Notes:

Class I share class. Funds rated by Morningstar can have up to four

ratings: a three-year rating, a five-year rating, a 10-year rating, and an

overall rating that is based on a combination of the others.

Read the methodology. |

Client David Peterseim, a

55-year-old retired surgeon in Charleston, S.C., said he was relieved the

financial adviser got out. He was disappointed “Morningstar didn’t have some

semblance to reality,” Dr. Peterseim said.

Michael Cuggino, president of the

San Francisco-based family of Permanent funds, said Permanent Portfolio’s

performance suffered as the price of gold and silver dropped.

Morningstar said Permanent Portfolio

was an “outlier” that “was designed as an inflation hedge; when precious metals

are in favor, it will score well, and when they’re not, this fund won’t do

well.” Major rallies in gold and silver ended in 2011, shortly before Mr. DeMuth

invested.

Other industry practices show how

much Wall Street’s system for buying and selling mutual funds revolves around

Morningstar ratings. Brokerage firms recommend high-stars funds to their

networks of tens of thousands of financial advisers, and those brokers in turn

put clients’ money in the funds. Large fund firms such as Fidelity Investments

and

T. Rowe Price Group Inc. allow investors to

filter out funds with low star ratings on their websites.

Current and former Morningstar

employees said some advisers use the ratings as a crutch.

“It’s a cover-your-ass type of

service,” says Samuel Lee, a former strategist at Morningstar. “An adviser can

say, ‘I’m going to put you in this fund, it’s a 5-star fund,’ …and if something

goes wrong the adviser can shunt blame to Morningstar.”

Scott Jennings, a former Morgan

Stanley financial adviser, recalled struggling last year to explain to a

company’s employees which funds they should choose in their retirement plans. He

decided to keep it simple and told them, “You only have two funds rated by

Morningstar—one’s a two-star and one’s a four-star. Go with the four-star.” He

could see a look of understanding flash across their faces.

At Morgan Stanley, “Advisers get in

trouble when they go against the grain,” Mr. Jennings said. “You isolate

yourself more if you sell something else rather than just go with what research

recommends.”

Morningstar said if advisers use the

ratings this way, “this is a fault with the users of the ratings, not the

ratings.... If an advisor wants to do proper due diligence, we provide a robust

set of information.” The firm’s marketing cautions that “a high rating alone is

not a sufficient basis for investment decisions.”

Morgan Stanley declined to comment.

Fund firms often cite Morningstar

ratings in their advertising—at times even out-of-date ones. AllianceBernstein

ran an ad for nine of its funds in a spring edition of Private Wealth magazine,

citing star ratings from September 2016. Two of the funds’ ratings had fallen by

the time the ad ran. AllianceBernstein ran a similar ad with the September

ratings in a Morningstar handout at the research firm’s April conference.

A spokesman for AllianceBernstein

said it made a “human error” in two instances out of “hundreds of digital and

print ads running that quarter.”

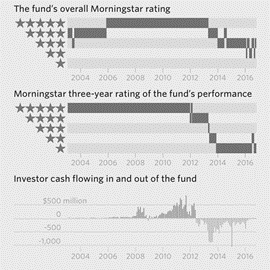

Dallas-based Hodges Small Cap Fund’s

retail share class beat 95% of similar funds in 2010 but had less than $100

million in assets. Late in 2011 Morningstar gave it a fifth star, and everything

changed, said Craig Hodges, who manages Hodges Capital Management.

Charles Schwab put the fund on its “Schwab

Select List.” Mr. Hodges and his brother Clark decided to advertise the star

rating on a billboard in Dallas/Fort Worth airport.

Hodges Capital paid more than

$10,000 to Morningstar for the right to advertise the stars, Craig Hodges said.

By the end of 2014, assets in that fund reached about $1.6 billion, according to

Morningstar data.

|

|

|

Notes: Retail share class. Funds rated by Morningstar can have up to four

ratings: a three-year rating, a five-year rating, a 10-year rating, and an

overall rating that is based on a combination of the others.

Read the methodology. |

Investment giants Vanguard Group and

Fidelity Investments pay upward of $1 million a year for licensing, data and

other tools from Morningstar, said people familiar with the arrangements. It’s

unclear how much is just for advertising.

Michael Rawson, who was a

Morningstar fund analyst for six years until spring 2016, said asset managers

who pay to advertise their stars are misrepresenting their funds because the

ratings are solely backward-looking.

“We know people misuse it. If we

know people misuse it, why don’t we do something about it?” Mr. Rawson said.

Morningstar said it publishes the

ratings because it believes they have investment merit, not for financial gain.

It said its intellectual-property licensing packages, which include the stars,

contributed just 4% of revenue in 2016.

Mr. Mansueto said employees are

encouraged to debate issues related to its products, but the efficacy of its

star ratings no longer comes up internally. “This is not a hot topic or even a

cold topic at Morningstar today,” he said.

As for the Hodges Small Cap Fund,

its performance has since turned down. Its rating has fallen to two stars from

five, and assets that had soared after the top rating have dropped by more than

half.

Aware of criticism of its star

ratings, Morningstar in 2011 launched a second rating system, currently covering

26% of fund share classes, in which the firm’s analysts do a more qualitative

assessment. Unlike the star system, analysts’ ratings often refer to likely

future performance. The firm said analysts’ ratings reflect its level of

conviction that a fund will “outperform its peer group and/or relevant

benchmark.”

The analysts give funds one of three

medals—gold, silver or bronze—or a ”neutral” or “negative” rating.

The Journal examined how these funds

performed in future years, as measured in their star ratings. It found that five

years after having a gold-medal rating from Morningstar’s analysts, funds had an

average rating of 3.4 stars for that five-year period.

Silver-medal funds were rated 3.3

stars for their performance over the following five years. Bronze-medal funds

had an average rating of 3 stars. In other words, while funds rated highly by

the Morningstar analysts did better, the differences among the funds weren’t

large.

A Morningstar spokeswoman said there

was a mismatch in how the Journal evaluated the performance of analyst-rated

funds because it relied on star ratings. She said unlike analysts, the star

ratings take into account a “load”—a sales fee—that some funds have.

The Journal analysis also found

Morningstar analysts’ ratings of funds were overwhelmingly positive. From

November 2011 through August 2017, the firm gave analyst ratings to about 9,200

fund share classes. Just 421, or 5%, received negative reviews. At the end of

August, only 1% did.

Mr. Mansueto said analysts tend to

choose better funds to examine, since they can’t review them all. “Investors

want to know what funds they should be investing in,” Mr. Mansueto said. “They

don’t care so much about what the terrible funds are.”

Morningstar recently started a third

“quantitative ratings” system that it says applies analyst screening to a

broader universe of funds. This one is likely to include more negative ratings,

executives said.

J.P. Morgan Chase

& Co. is among asset managers that regularly send portfolio managers to talk to

Morningstar analysts about the merits of their funds.

BlackRock Inc. has a team that works to

persuade Morningstar analysts of the merits of various funds, according to

people familiar with the matter.

They added that BlackRock CEO

Laurence Fink met with Morningstar analysts early this year to discuss the

firm’s ratings. In May, Morningstar upgraded to positive BlackRock’s “parent

pillar” rating, an evaluation in which analysts are looking for factors

including an alignment of interests between fund shareholders and those who

manage the funds.

A BlackRock spokesman said its team

that works with research providers “is focused on providing transparency,

education and information about our products to facilitate informed decisions.”

Morningstar said BlackRock had

changed how portfolio managers were paid in a way that led to their having more

of their own money invested in BlackRock funds. “We followed the same process in

evaluating Blackrock’s standing as a parent that we do with any other firm,”

said a Morningstar spokeswoman.

Mr. Kapoor, the Morningstar CEO,

said analysts operate independently from fund companies and without influence

from management despite frequent angry calls executives must field. “We prize

our independence,” he said.

Morningstar’s application to the

Securities and Exchange Commission for permission to launch nine mutual funds of

its own has led some critics to cry conflict of interest. The Morningstar

spokeswoman said the firm is in a quiet period related to the filing,

restricting what it can say, but she said the firm’s analysts sit “in a separate

entity” from Morningstar Investment Management, which would oversee the

company’s funds.

The Journal spoke with more than

three dozen executives at asset-management firms large and small about

Morningstar. Few would go on the record.

Several years ago, some were unhappy

when Morningstar changed the way it calculates its “stewardship grade,” which is

supposed to measure the corporate culture of each fund company. Executives from

fund companies viewed the change as the latest example of Morningstar acting

unilaterally and without explaining itself.

The money managers drafted a

two-page letter to Morningstar that accused the company of “bullying” fund

companies and running a monopoly, according to people familiar with the letter.

“The nature of what we do is going

to end up alienating some portion of the industry,” said Jeffrey Ptak,

Morningstar’s global director of manager research. “That’s not something we

relish but it’s part of our job.”

When the time came for the

money-management firms to put their names to the letter, they balked. The letter

was never sent.

The

Morningstar Mirage

By

Kirsten Grind,

Tom McGinty and

Sarah Krouse

Oct. 25,

2017 11:51 a.m. ET