Your Money

|

Gretchen

Morgenson

Why Buybacks Aren’t

Always Good News

By

GRETCHEN

MORGENSON

NOV.

12, 2006

ONE

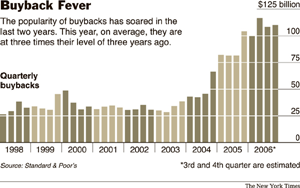

force behind the stock market’s recent strength has been the flood of

money that corporate America has poured into share buyback programs.

According to Standard & Poor’s, the companies in its flagship

500-stock index are on track to repurchase more than $435 billion

worth of their shares this year. That’s significantly more than the

$349 billion repurchased in 2005 and more than triple the $131 billion

in shares that were bought in 2003.

Many investors

applaud the buyback binge, considering these programs entirely beneficial. After

all, buybacks support a company’s stock price and buoy per-share earnings by

reducing the amount of stock outstanding.

But less obvious

to investors are the downsides associated with buybacks. By artificially

inflating a company’s earnings per share, repurchases can mask business

slowdowns, for example. Companies can hurt their financial positions by putting

scarce cash into repurchases. And when buybacks are used to offset multitudinous

stock option grants to corporate executives, an even more pernicious outcome can

occur: the purchases may actually destroy shareholder value by forcing companies

to essentially buy stock in the open market at high prices to cover shares sold

at lower prices to executives.

Furthermore, it

may not surprise you to learn, buybacks can wind up bolstering top executives’

compensation. A new study by Jill Lehman, a managing director at the Center for

Financial Research Analysis, and Paul Hodgson, a senior research associate at

the Corporate Library, makes these and other risks clear.

“If a company is

generating negative cash flows prior to the buybacks it seems that they

shouldn’t also be using cash to buy back those shares,” said Marc A. Siegel,

director of research at the C.F.R.A. “With all the buybacks going on, we thought

it would be interesting to marry up which companies might be executing fiscally

unwarranted repurchases with companies where executives are being compensated on

metrics that are benefited by buybacks.”

Thankfully, the

study found only three companies that had negative cash flows over the past

three years before accounting for the costs of their share reductions. They were

Dominion Resources, Ryder System, and the Southern Company.

But the story

definitely becomes more interesting as one looks at compensation practices among

S.& P. companies making repurchases and generating negative cash flows as a

result for the last two years. A total of 78 companies meeting those

requirements popped up.

Of these

companies, the study found, 33 used an earnings-per-share measure to analyze

performance when determining executive pay — that’s about 42 percent. Among the

S.& P. 500 as a whole, only 28 percent of the companies used that measure.

Per-share measures, of course, are hardly exact barometers of financial

performance because they can be greatly influenced by the reduction in shares

outstanding associated with buyback programs.

This disparity

makes one wonder whether some repurchase programs have been instituted to

generate higher levels of earnings per share, thereby ensuring the payout of

short- and long-term incentives.

The study found

that chief executives at 89 percent of these 78 share-repurchasing companies

received an annual bonus in 2005, compared with 78 percent of chief executives

for all companies in the S.& P. 500.

In addition,

companies in the group that use per-share performance measures were more likely

to have paid a bonus to their chief executives last year. At the 33 companies

using such measures, only 3 percent did not pay out an annual bonus in 2005; by

comparison, 13 percent of the companies in the sample that did not use per-share

measures failed to pay a bonus.

The median bonus

among negative-cash-flow companies that have bought back shares was also a bit

higher than it was in the S.& P. as a whole: $1,565,050 versus $1,487,800.

While earnings

per share is a commonly accepted measure of short-term corporate performance,

the study’s authors questioned its effectiveness in assessing long-term value

growth. Nevertheless, some of the buyback companies use earnings per share to

assess performance for both the short term and the long term, “a very poor

governance practice resulting in the same set of performance achievements being

rewarded twice,” the study said.

Eight companies

did this: Eli Lilly, Hershey, Huntington Bancshares,

Masco, Pitney Bowes, Procter & Gamble, Pulte Homes and

Robert Half International.

The study said

that none of the companies that engaged in share repurchases and used an

earnings-per-share measure discussed in their proxies the impact of buyback

programs on their pay calculations. Home Depot, a company that has been

criticized for its pay practices, did the right thing starting in 2004 by

excluding the effects of share repurchases during the performance period when

measuring earnings per share for compensation purposes. But this year, the

company said its long-term incentive plan would no longer be adjusted for the

impact of share repurchases.

The chief

executive’s incentive plan at Countrywide Financial, a mortgage lender

that has engaged in buybacks, seems designed to get a big boost from

earnings-per-share growth, the study said. While other executives at the company

receive pay based on growth in its return on equity, Angelo R. Mozilo’s bonus is

based solely on earnings per share. Mr. Mozilo has received bonuses worth $56.7

million in the past three years. Countrywide did not return a phone call seeking

comment.

As buybacks have

ballooned, the study said, some companies conducting the programs have changed

their pay-for-performance targets to include earnings per share. In 2004, for

example, Eli Lilly moved from a bonus plan that assessed changes in economic

value at the company to one that measured moves in earnings per share.

Philip Belt, a

Lilly spokesman, said his company’s buybacks were so small relative to its

market value that linking the program to executive pay was ludicrous. “In the

last two years, our total buybacks have been approximately half a billion

dollars, a very small amount,” he said.

Spokeswomen for

Masco and Hershey said that their compensation committees consider the impact of

share buybacks when they set executive pay. And a Ryder spokesman said that the

company’s negative cash flow position was a temporary imbalance because recent

capital expenditures will generate revenues from contracts over time. He said

the buyback program offsets stock grants and employee share purchase plans at

the company.

Clearly, not all

buybacks are created equal — at least for investors. And as the numbers of

buybacks grow, the manner in which they may mask a company’s true performance

becomes more problematic.

“We have a

concern here that investors may not appreciate the full impact that the buyback

has on the earnings per share,” said Howard Silverblatt, senior index analyst at

S.& P. “When the buybacks stop, where is the growth going to come from?”

Adding to the

anxiety about repurchases, Mr. Silverblatt said, is the fact that the shares

have not been completely retired. The company can bring them back onto the

market at any point; this would dilute existing shareholders’ stakes.

“What is the

company going to be doing with these shares?” he asked. “It is an enormous

amount of assets under control of management that has not been retired and could

be put back into the market.” Using cash to pay dividends would be far

preferable, of course, especially given the lower tax rates that apply to such

payments. But managements are wary of dividends because, once they grant them,

shareholders come to expect them.

Buyback programs

look great from a distance. Up close, however, the picture blurs. More

significantly, they may be a way for some corporate managers to think, once

again, of themselves first and their owners second.

A

version of this article appears in print on , on Page BU1 of the New York

edition with the headline: Why Buybacks Aren’t Always Good News.

© 2016 The

New York Times Company